The Battle of Wizna

The Battle of Wizna refers to a battle fought in the initial stages of the invasion of Poland. Taking place from September 7-10, 1939, the fight marks the heroic stand of the Polish army against overwhelming odds. Led by Captain Władysłav Raginis, the Polish soldiers – numbering between 350 and 720 men – held off the Wehrmacht – numbering over 40 000 soldiers – for three days.

September 1939

The German invasion of Poland began in September 1939. Poland was to also soon be invaded by the Soviet Union, and within six weeks would be divided by those two great powers.

On September 7, the XIX Army Corps of Heeresgruppe Nord, part of the German 3rd Army under General Heinz Guderian, was quickly advancing to try and cross the river Biebrza, a tributary of the River Narew, east of the town of Wizna. By doing so, it would be able to encircle the Polish Narew Corps and then close in on Warsaw from the Northeast.

Since early 1939, the Polish Army had begun building defence works around the strategic crossing where the Biebrza and Narew met, when the possibility of war really began looming. The crossing was surrounded by swamps and bogs, so a system of echeloned bunkers and pillboxes on the hills overlooking the rivers would be a serious threat to any army trying to make a crossing.

The problem was that the defence works were not complete as the German Panzer Corps approached. Only 12 major bunkers were battle ready and there were a few machine gun pillboxes spread out over two actual lines of defence. The big flaw though was that the system did not have any larger anti-tank guns or mortars, and with a force of 350 tanks approaching, this flaw was now a major problem.

The Polish defenders, commanded by Captain Raginis, had quickly assembled some anti-tank obstacles, prepared the forward approach with trenches and barbed wire, and mined the riverbanks.

Raginis himself had chosen the bunker in the middle as his command post, but he must have known that with only six 7.6 cm guns, a few dozen machine guns and only a pair of anti-tank rifles, he could not hope to hold out forever. As German planes dropped propaganda leaflets from the skies urging the Poles to surrender, Raginis vowed that he would die trying.

The battle commences

The first skirmish between German and Polish recon units was fought for the village of Wizna on September 7, but the Poles gave up what was an undefendable village without serious resistance. So even at the beginning, it seemed as if the Poles had been routed, but they hadn’t given up and they hadn’t fled. They had retreated back over the river into the safety of their bunkers.

The Germans pursued them, but Polish engineers blew the bridges to stop them. The battle had begun.

German heavy artillery was brought up and pounded the Polish positions throughout the remainder of the day. The Polish artillery was no match for this and was forced to withdraw, but the Polish bunkers held. Stuka bombardments from the air also failed to break them, since the walls of those bunkers were over one-and-a-half metres thick and reinforced with steel plates.

German assault troops came next, attacking over the two days, but as soon as they crossed the river, they were hit by machine gun fire from the forward Polish pillboxes. Suffering heavy casualties, they were forced to retreat time and again. However, on the evening of September 8, as German tanks began to cross, and with no adequate measures to deal with them and overall limited ammunition, the Polish infantry withdrew from their forward lines near the river to the safety of the bunkers. The German tanks rolled over and through those lines, but their guns could not penetrate the bunkers, nor could they provide enough cover for the infantry to follow. It was a somewhat bizarre stalemate.

Yet without help from reinforcements or any real anti-tank capability, the Polish soldiers were now trapped.

Another flaw in the bunker system now became apparent. The major bunkers were sometimes too far away from each other to provide adequate support, and could not cover each other’s blind spots, so it turned out that the Germans were able to attack and isolate them one after the other.

The first bunkers to fall were the ones just across the Narew River. Concentrated heavy artillery bombardment and advancing tanks forced the defenders to flee or else be completely encircled. The other bunkers held out until September 10, but in the early morning of that day, after three days of holding off 40:1 odds, the Poles faced defeat, as small platoons of German combat engineers could finally take out the damaged bunkers with explosives, with tanks providing covering fire. One after the other was destroyed and the Germans closed in on Captain Raginis’ command centre. By this time, most of his company was reportedly either dead or wounded, and the ammunition was nearly finished.

The first bunkers to fall were the ones just across the Narew River. Concentrated heavy artillery bombardment and advancing tanks forced the defenders to flee or else be completely encircled. The other bunkers held out until September 10, but in the early morning of that day, after three days of holding off 40:1 odds, the Poles faced defeat, as small platoons of German combat engineers could finally take out the damaged bunkers with explosives, with tanks providing covering fire. One after the other was destroyed and the Germans closed in on Captain Raginis’ command centre. By this time, most of his company was reportedly either dead or wounded, and the ammunition was nearly finished.

Captain Raginis finally ordered his men to surrender their weapons since the battle that they could not win was effectively over. True to his word, though, Captain Raginis died by clutching a grenade to his body in his command bunker. They had held out for over three days against some of the strongest forces in the entire German Army. That is the story of the Polish Thermopylae.

According to some, Guderian threatened to shoot Polish prisoners if they did not give up, though that seems unlikely, since the battle was already won and it would have been out of character for Guderian. This is debated as German battle records don’t mention the engagement and Polish sources differ on the strength of the defenders. There isn’t a concrete number of casualties to report and what happened to the Polish prisoners that were taken in the battle is unknown.

The will of Polish defenders

Despite the outcome of this battle, there are several other shining examples of determined and excellent Polish defences against overwhelming odds during the German invasion. The Battle of the Bzura, the defence at Hel Peninsula, even the remarkable evacuation of LOT, the Polish national airline, of its planes, machine tools and factory equipment to Bucharest in the face of dual invasion, all attest to the grit and will of the Polish defenders. Many are not familiar with this, because during the war the Allies crafted a narrative of a heavily inferior Poland, easily overrun by the mighty Germans in order to reinforce how aggressive and dangerous Nazi Germany was. Because of this, the idea of Polish horsemen fighting hopelessly against tanks, dive bombers and heavy artillery was reinforced in films and articles, and has remained to be the popular interpretation of the beginning of WW2, but it wasn’t so.

Post invasion

After the invasion of Poland, and even with the speed of its success, Adolf Hitler’s generals warned him time and again to wait before attacking in Western Europe, which he had originally planned to do in October 1939. This was because the strong Polish defence had brought their own weaknesses to light, and they did not think they were strong enough yet to win.

If you prefer a visual interpretation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode: 40:1 – The Battle of Wizna.

Another Polish last stand

In mid-September 1939 and Poland was burning. The German invasion had shattered the main Polish defences in the west and began encircling Warsaw from the northeast. Long trails of refugees were making their way from the big cities, as artillery rumbled in the distance. Smoking craters remained where German dive bombers had struck, and dead soldiers and the bodies of civilians littered the roads. The destruction of the sovereign Polish state was drawing to a close.

Still there was no sign of surrender. By September 16, the remaining Polish forces were ordered to withdraw towards the Romanian border. There they were to re-organise and prepare for a new offensive against the invaders. The Polish Generals aimed for a long-term defensive battle. Their strategy was to hold out long enough for their Allies to intervene. Those plans, however, were rudely shattered as Soviet troops began crossing the border in the east. At first, there was the faint hope that the Red Army might have come to their aid, but as Polish troops were fired upon and many of their officers were arrested or even executed, it became clear that this was just the final nail in their coffin.

Immediately, the Germans and Soviets began establishing a line between their forces, preparing for a new, post-war border. True to the secret protocol in their recent pact, the Polish state was to cease to exist, and neither would tolerate Polish ‘agitation’ in their zone, which meant that resistance was to be mercilessly crushed.

The Polish resistance perseveres

The last remaining Polish forces found themselves trapped in an ever-shrinking cordon between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army. Still, throughout the country, small Polish holdouts kept on resisting. They were isolated and endured overpowering aerial and artillery attacks for days on end, but until they ran out of ammunition and supplies, they would not surrender. One such force was the freshly re-organised Independent Polesie Operational Group under Brigadier General Franciszek Kleeberg. The SGO Polesie had been tasked with protecting the Polish rear and acting as a mobile reserve in the east. Since the Soviet invasion though, they had been repeatedly fighting off attacks by the Red Army. In fact, they had given the Soviets such a beating that the Red Army refrained from further attacks, so the Polesie was on its way westwards to reach Warsaw. From what they knew, the capital still resisted the German siege. Shadowed by the Red Army, the SGO Polesie made its way towards the Vistula. On their march they were joined by scattered soldiers, leaderless reservists and civilian volunteers, bolstering their numbers to around 18,000 men.

On September 28, they had just reached the town of Wlodawa on the Bug River, as news of Warsaw’s capitulation broke. The government went into exile and Modlin Fortress, guarding the approach to the capital from the north, was about to capitulate as well after 16 days of resistance. With the last great fortress gone, and nearly all of the Polish forces either encircled or overrun, it was futile trying to reach the capital. Kleeberg instead chose to make for Deblin and gather whatever ammunition and supplies they could find on the way. They still wanted to prolong the fight as long as possible. Throwing down their arms and surrendering was not an option, and it was still possible that the Allies would come to their help in some way. As long as they kept on fighting, the war was still on and they remained free men, not prisoners walking into slavery. If they did not surrender, they were not beaten and Poland still existed. In each village they passed on their way, folk gathered, blessing them and waving them goodbye.

Halfway to the Vistula, in the wooded area of Kock, the SGO Polesie was spotted by German motorcycle scouts. The scouts belonged to the German 13th Motorized Division under General Paul Otto, which was currently engaged in mopping up operations southeast of Warsaw. Otto assumed that the fall of the capital would have demoralised the Polish soldiers to such a degree that they would be incapable of putting up much of fight. He would soon find out how wrong he was on that one.

The tenacity of the Poles

In the early morning of October 2, the first German halftracks and trucks closed in on Kock but immediately came under heavy fire. Kleeberg had ordered his troops into a defensive belt. The area was characterised by small villages, lakes and forests, which gave the Poles enough space to disperse their strong-points and control the approaches. They only had a handful of artillery pieces and not even enough bayonets for the infantry, but they could still count on the formidable Polish cavalry squadrons that could quickly move from position to position and threaten the German flanks. Seeing cavalry, like the Polish Uhlans, engage German motorcycles was certainly a strange sight, but the swift and concentrated cavalry advances proved devastating.

In the afternoon, the Wehrmacht returned with artillery, but was unable to knock the Polish defenders out of their positions. And Kleeberg had ordered ammunition and supplies to be stored deep in the forests to prevent them from being spotted from the air.

By October 3, the Germans had realised that the Polish resistance was way more tenacious and better organised than they expected. More troops were moved forward in an attempt to split the enemy in half. But Kleeberg had anticipated such a move, and his spread out forces kept denying the Germans a concentrated advance. German motorcycles could circle around the villages, but the villages themselves were too well defended. Fighting over cemeteries and churches caused the Germans heavy casualties. Disorganised, they were about to retreat once more in the evening, and Kleeberg saw an opening.

He immediately ordered a counterattack. Both sides clashed well into the night, and although the Polish attack was ultimately stopped, the Germans had been dealt a bloody nose. In fact, the 13th Motorized Division had suffered such heavy casualties that it had to lay low for the whole next day.

On October 5, Adolf Hitler appeared in Warsaw. The excessive victory parade lasted all day long, but not that far away from the capital, the fight for Poland was still going strong. The Germans prepared for a general advance to encircle Kleeberg’s forces. At first, the attack was fierce, and the Poles were pushed back under the weight of German artillery fire. But as the German infantry entered Adamow forest, they were met with strong Polish resistance. With grenades and bayonets the German soldiers were driven out and into the open, and there, they were struck by the Polish Uhlans. For Kleeberg, it was a sight to behold. Once again, and for the last time, the Germans were routed and fled in panic before the Polish cavalry. But despite the Polish tactical victories, their strategic position looked grimmer than ever. They had suffered irreplaceable casualties. Horses, men and motorcycles littered the roads.

Time to surrender

In the evening, the remaining commanders of the SGO Polesie gathered in a small farmhouse to discuss their fate. They were nearly out of rifle ammunition, food and bandages. They were isolated, exhausted, without hope for relief, and the Germans were bringing in reinforcements. Ultimately, Kleeberg decided that it was time to surrender. No one could say that they hadn’t done their duty to their country. On the night of October 6, the last shots were fired. At 2 o’clock they sent an envoy to the Germans to offer surrender, an offer that was gladly accepted. Still, the Poles hid their weapons around the area, to hopefully later continue the fight underground. Some soldiers fled in civilian clothes or hid away. The spirit of resistance remained, even if the last Polish army would not.

In the early morning, shortly before marching into captivity, Kleeberg addressed his soldiers for one last time: “You showed courage at a time of doubt and you remained faithful to your country until the end. Today we are surrounded and running out of ammunition and food. Continued resistance offers no hope, but will only shed soldiers’ blood, which could still be useful. Today, I take it at the hardest time, ordering you to stop further pointless bloodshed, so as not to waste soldiers’ lives. I thank you for your courage and obedience, and I know that you will take up arms again when you are needed. Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła – Poland is not yet lost.”

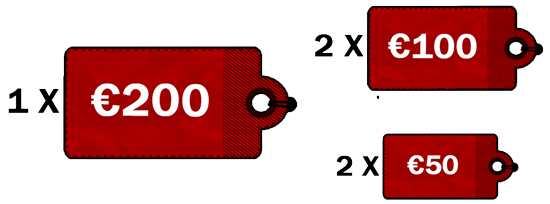

Inspired by the Battle of Wizna, we paid tribute to the bravery of the Polish soldiers with the song 40:1‘ from our album, ‘The Art Of War’. Take a look at the lyrics we wrote here.

If you prefer a visual interpretation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode: 40:1 Pt. 2 – Another Polish Last Stand.