Angels Calling

It has often been said that when Generals prepare to fight a war, it is the last war, the one that came before. This certainly seemed true for the Great War, when the powder keg of European ambitions and arrogance exploded in July and August 1914. The soldiers marched out in the old formations of lines and squares to meet their enemy in open fields. Officers with shining sabres and white gloves led cavalrymen clad in iron breastplates, feathered caps and lavishly ornamented overcoats. Red trousers, spiked leather helmets, and glittering bayonets went out in hopes of glory and quick victory, because this was how you were supposed to fight a war.

It all vanished in the terror of guns and canons. Warfare had become industrialised, and its most evident symbols of destruction were the machine-gun, whose firepower could replace that of a whole company, and the barbed wire, a simple agricultural tool to herd cattle, now dooming men to be trapped within a killing zone. Both are rather simple tools, made in factories far from the frontlines, but now able to overpower everything that human flesh sought to achieve.

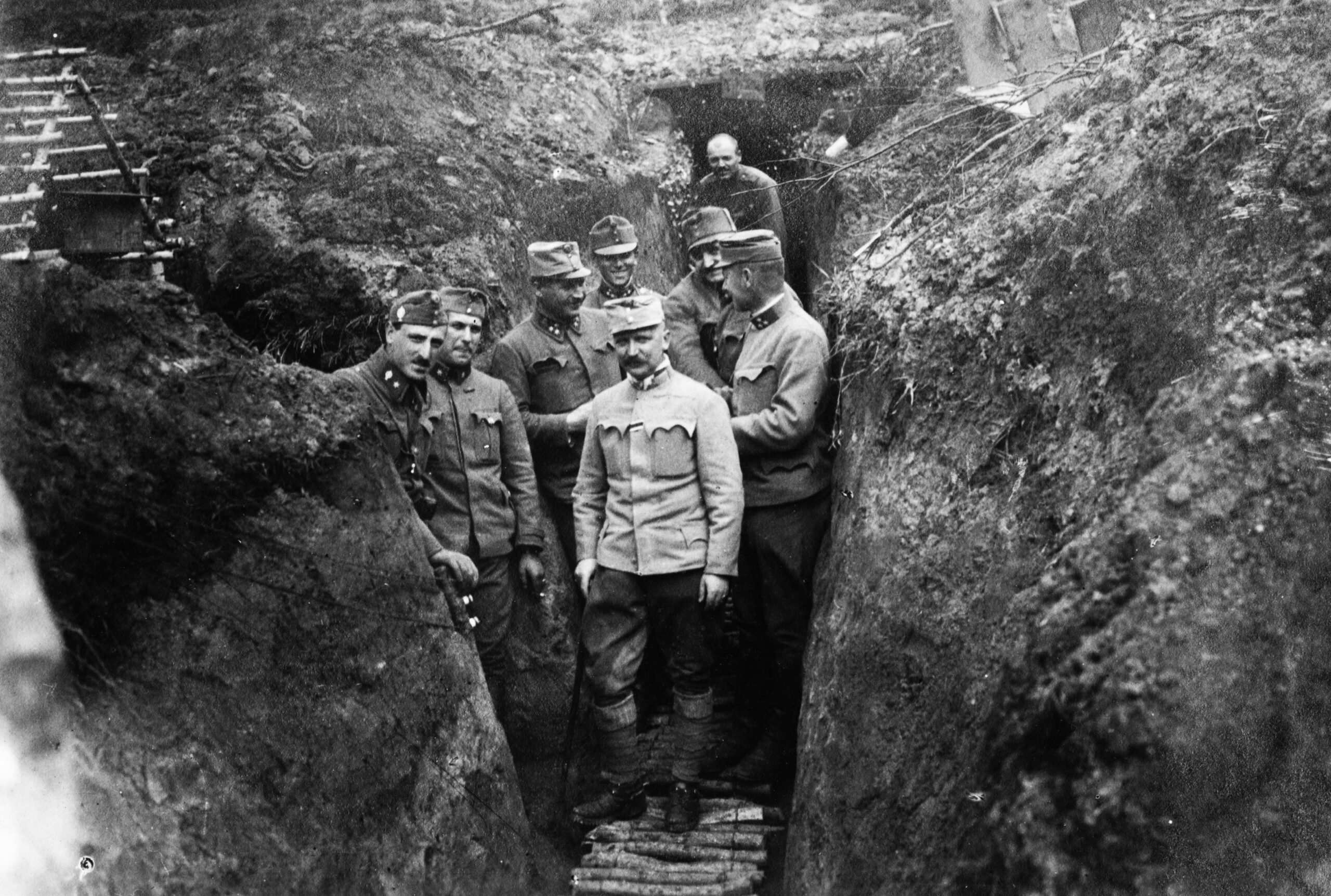

Instead of the great glorious battles, the Waterloos of the past, armies now faced an unconquerable no-man’s land stretching out between them. Gallant bodies of troops, charging once more and yet once more into the breach, all met their fate, hanging upright on belts of barbed wire, bullet ridden, silently decaying there for months. Horses were as useless as men in the churned-up ground of no-man’s land, and the invention of the protective tank was still far in the future. To escape the inevitable death from afar, men had no choice but to dig and dig deeply, out of sight, and out of reach of the mighty guns.

The nature of industrialised war

War was not about geography anymore; it was not about capturing cities or economic strong points. The only way to win in the deadlock was to kill as many of the enemies as possible until breakthrough could be achieved. The nature of industrialised war was that the defence had the clear advantage over the offence. An entrenched position was simply more effective at killing the enemy. Hundreds of thousands of dead men littering the space between the trenches were proof of that. Consequently, the war slowed down and soldiers went deep beneath the earth, into their trenches and dugouts. There, they waited for the dark. The day was too dangerous, and even taking a quick glance over the parapets was gambling with death.

Instead, soldiers confined themselves to a life within the trenches. Daylight was a game of hiding and waiting, while firing from safety with artillery, mortars and grenades. Movement was very limited. Men actually slept more during the day than they did at night. However, once the day ended, when dusk came and the sun went down, the men went to work. Soldiers crept out into no-man’s land to dig saps, repair trenches and lay new barbed wire. Food and water were brought forward and medical orderlies could finally reach the contested front lines. The wounded in no-man’s land, moaning and screaming for help, could hopefully be retrieved by their comrades, and those who had been trapped by the daylight in the shell holes of the killing zone, had a chance to make it back to their own lines.

“I pressed myself to ground and pulled in my head and legs, as the bullets swept over me. Just as unpleasant were the glowing lumps of magnesium by the falling flares, that burned down close besides me. Since the moon had disappeared behind clouds, I soon lost track of everything. I knew neither where the English (sic) nor the German side was. At times a bullet, fired by one or the other side, was sweeping across the ground, dangerously close. I was prepared to meet any English hail with a hand-grenade, but to my relief, it was my own men, coming to retrieve my assumed-to-be-dead body.” – Ernst Jünger, In Stahlgewittern

As the lost and wounded were brought in, others went out into the dark to fight. Snipers crawled on their bellies into no-man’s land, looking for a lair from which they could deal death into the enemy’s hideout the next day. Combat patrols went out to get close to the enemy, to find and engage their sappers, or simply patrol the dead-zone against enemy raiders. Raiding parties with blackened faces, clubs and pistols were sent out into the night to prey on tired sentries, to take prisoners, to steal information or to destroy what they could in a deadly game of cat and mouse, of hunter and prey.

In fear of those men, sentries had to stay awake. Easier said than done. Notoriously deprived of sleep, the men waited for hours, staring into the dark, anxiously listening for footsteps, whispers or anything that rattled against the wire. Armed with magnesium flares, they remained ready to alarm their comrades, and any such alarm was immediately met with illuminating flares and machine gun fire, tearing the unlucky raiders apart.

“At dusk we got to work; I marked out the gun-pits by torchlight and the cold glare of occasional star shells, and soon all were digging. It was an eerie and unpleasant night. It rained at times. Odd shells fell, always seeming nearer in the darkness. (…) About midnight a hell of a row broke out in front with heavy machine-gun fire. Verey lights went up and a stream of our S.O.S. shells flew close over our heads. The men seemed more frightened than I was, being all on their own in the dark, wondering if the Boche might be coming at them over the ridge.” – Huntly Gordon, The unreturning army

Darkness was an ally

The night was also a chance to prepare for coming offensives. The phrase “at first light” is often attributed to such offensives, but most of them started way before the first light, since the dark was the attacker’s most precious ally. Whole regiments were changed at night, which took hours if not all night, since traversing the trenches was like wandering through a maze in the dark, because even the slightest shadow or the smallest light source would attract the attention of the enemy gunners. Artillery was still very active during the night, harassing the enemy, depriving them of sleep.

“Just look at our artillery. Just look at it, at those countless flashes. See how they stab at the darkness from their hiding places, not in dozens but in hundreds, and yet these are only the heavies, the lighter guns are well up and we cannot see them. The whole place seems ablaze as far as the eye can see: flash after flash, some singly, some in groups, but isn’t it all beyond description, beyond belief, even beyond imagination?” – Lieutenant Cyril Lawrence; Peter Hart: The Great War

Even those men lucky enough to have a cosy spot that was not just a muddy shell hole, a hole in the wall of a trench, or a dangerously shaky dugout that threatened to swallow a man whole with the next impact, couldn’t find sleep easily. Fear and memories were maddening, and only the hope of returning home one day was what kept many of the men sane enough to carry on. Photographs and letters from family and loved ones were cherished treasures, which sometimes decorated the small space of the dugouts, where the men got their 2-3 hours of sleep until woken again for guard duty. Others lost themselves in silent prayers or memorised holy verses. Sleep was a luxury for most of the common soldiers. And it was all anonymous. Who remembers the single soldier, lying in a water-filled shell hole throughout the night, shivering from the freezing temperature, only to fight the coming day?

“It was a quick, easy death. I dragged my fallen comrade to a shell hole and covered him with my groundsheet. There was a battle raging off to the right: it was now broad daylight. I now had to hang on for another eighteen hours, soaked to the skin. My boots were full of water, my coat leaked and everything was dripping. I was shivering and freezing from cold and I could not gather my thoughts together coherently. The day dragged by. After an eternity, evening drew near and, with it, relief. We now had to carry our fallen comrade back to the rear with us. (…) There could be no question of sleep that night. At long last dawn approached and we dragged our weary frozen limbs into our accommodation. I lay down on a hard bed and fell asleep. I slept and then I dreamt – not of the war, but of love at home and the love of a young woman.” – Gefreiter Hinrichsen; Jack Sheldon: The German Army at Passchendaele

But even if they got used to the harsh conditions, to the shelling, maybe even to the rats or the omnipresent plague of lice, there was still one enemy from which they could not take shelter – Gas. In the front trenches it was mandatory to keep a gas mask at the ready, because once under fire there were but seconds that lay between life and an agonising death.

And at night, in total darkness, it was easy to panic and lose everything. And panic was always close by, because they knew that unseen snipers were moving around, searching for a spot from which they could kill them the next day. They knew that men with clubs and knives were wandering around in the dark, waiting for the chance to spill blood. They knew that comrades, maybe dear friends, were lying out there outside their reach, too weak to cry for help, slowly bleeding out. And they knew that a new day would eventually come, and with the sunlight, that a new day of fighting, killing and dying was upon them. They would find their enemies and their enemies would find them with bullets bearing their names.

If you’re interested in a more visual interpretation of the above story, watch our Sabaton History episode, Angels Calling – Trench Warfare:

Angels Calling Part II

The days in the trenches were best described as long periods of boredom and waiting that were suddenly interrupted by brief periods of violence and chaos. The trenches were on all fronts of the war in all climates, and they were not just ditches in the ground. In over 1,000 kilometres on the Western Front from the North Sea to the Swiss border, for example, the simple trenches soon developed into a complex and sophisticated network, supported by dugouts and redoubts in an interlocking, interconnected system.

Despite the common myths, the soldier in the forward firing lines would not typically remain there for long. The constant shelling and sniper fire eroded morale, and discipline suffered accordingly. Men and weapons were consumed by filth. The unburied corpses and the fleas would spread disease, and the fighting spirit sank from the constant stress and sleeplessness. Even during the big battles, when soldiers were virtually trapped in their dugouts and bunkers, it was still expected that there was a somewhat regular rotation system in place that cycled the men through the lines.

In the firing trench

In early 1915, most battalions could be expected to remain in position for two weeks before being replaced. That time was halved a year later. In 1917, the usual period of time for soldiers to be in the firing trench was between 4 to 6 days a month. From there, they went to the supporting line, then later to the reserves, and finally, all the way back to the billets. Returning to the rear, the men entered the world of military logistics. Here they were provided with regular baths, church services, concerts, cinemas, brothels and of course a postal service. The German postal service alone was recorded to have sent over 28 billion letters, packages and postcards back and forth from the front to home. All those things were of vital importance.

The widespread army mutinies of 1917, in France, Italy and Russia, were to a large part caused by the unwillingness of the common soldier to return to the hellish conditions at the front, although there was also an element of being unwilling any longer to be cannon fodder in highly wasteful offensives. They wanted the rotation system improved, more frequent leaves to the rear, and an end to mail being withheld as a punishment.

Most historians agree that the major reason why the British Army did not suffer any major mutinies in the war, was because they kept their logistical system running smoothly, which kept the men in better spirits.

The British introduced a nutrition model that provided their soldiers with 4,000 calories a day. Meat, bread, fresh and dried vegetables, of course biscuits and tea, jam, sugar, milk, and even luxury items like tobacco and rum, were never in short supply. This was a diet that the Germans and Austro-Hungarians could have only dreamed of. But that was 4,000 calories a day for a mobilised army of over 2.6 million in 1916. And that number only kept rising to never-before-seen numbers. They had to dress all those men, supply them with weapons and ammunition, repair their boots, manufacture helmets…

“Every infantryman wore “fighting order”. The normal equipment, including steel helmet and entrenching tool, less the pack and greatcoat; with rolled groundsheet, water-bottle, and haversack in place of the pack on the back. In the haversack were small things, mess tin, towel, shaving kit, extra socks, message book, today’s ration, extra cheese, one preserved ration, and one iron ration. Two gas helmets and tear goggles were carried, also wire-cutters, field dressing and iodine. Officers and NCOs carried 4 flares. Moving from dump to dump, the men picked up, besides 220 rounds of small arms ammunition, two sandbags and two Mills grenades, these last only be thrown by trained bombers. Each leading company also took 10 picks and 50 shovels.” – British Official History of the Great War, 1916, p.313-314

This quote is often used to describe how overburdened the British soldier was at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, but it also highlights how many different tools were expected to be carried into a battle of unknown duration. Each nation had to mass produce such common things in the millions, and also keep up a functional logistic and supply system that could bring those things from the factory to the frontline. And this was just 1916, when the age of the mass-producing war economy was just beginning. The year of battles, as it was called, had produced such an unsustainable number of casualties for everyone, that the nations looked to the industry to fight the war for them.

The new war industry

The British, of course, stood with their backs to an empire. The Imperial Munitions Board continuously reached out to its colonies and dominions for help. They imported tin from Malaya, chromium from South Africa and lead from Australia. Canada and India developed their own armament industries and produced millions of shells and cartridges.

Everything else was purchased. Pyrite from Spain, aluminum from the United States, and most importantly, sodium nitrate from Chile. Actually, the allied war effort became so dependent on the nitrate salts from Chile, which were essential for the propellant for artillery shells, that in the busy moments of the war, just one lost shipment at sea could have halted the entire shell production of all allied factories.

Between April 1917 and November 1918, the British manufactured 121 million shells through this system, but even they were outclassed by the French, who produced nearly 150 million. France’s GDP was not even half of that of Britain, but its industry was permanently working on its absolute limits. In 1914, around 50,000 people had worked in its armament industry. That number rose to 1,675,000 in 1918. It produced everything en masse for the war effort, and yet also supplied the war in the Balkans and sent guns and shells to Russia until the revolution. By the end of the war, France had built a giant new industry around heavy guns, aircraft and tanks, with Renault being able to produce 278 light tanks in just the month of July 1918. France did not only have the largest air force in the world by the end of the war, but also the industry to sustain it.

The same went for Italy to an extent, which had rapidly built and modernised its war economy by mobilising hundreds of thousands of men and women into the factories of Caproni, Ansaldo and Fiat. Italy was one of the least industrialised nations in Europe before the war, but now kept large armies supplied on its own. It could lose 3,000 artillery pieces in the battle of Caporetto in 1917 and have them replaced not even a year later for the counter-offensive. However, the factories were overseen with military discipline. Strikes were simply forbidden, and “safety-regulations” was a term you would only stumble across in an underground socialist newspaper.

The Hindenburg Program

In Germany, the Hindenburg Program of 1917 had put the whole German economy and large parts of Austro-Hungarian industry under centralised control. It demanded a doubling of munition production and a tripling of machine-guns and artillery. The German War Department allocated all available raw materials and substitutes for a single purpose – continuing the war. The German industry suffered heavily from the British economic blockade, but it was still able to match the production of the allies when it came to the tools of trench warfare. However, it also had to supply its allies with aircraft, artillery, helmets and rifles. Austria-Hungary was shaken by 1918, Bulgaria was close to economic collapse, and the Ottoman population was starving. But the fighting in the trenches had to keep going, and they looked for affordable technical innovations to achieve that.

Although the Livens-gas-projector had been invented in Britain as a simple tool to kill as many Germans as cheaply as possible, it was the German industry that supplied a whole system of gas-warfare. In 1918 alone, for the spring offensive, they produced 18,700,000 gas shells. By the end of the war, it is estimated that over 110,000 tons of poison gas had been released over the battlefields of Europe by all nations combined. And it could have been way more. The US was preparing for gas warfare as well, and while the Germans could produce around 18 tons of gas a day, the US calculated that it could produce 200 tons a day in mid-1919.

But despite the innovations, what the German army could not mass produce were horses and lorries. The age of cavalry was at its end, but all armies still relied on draught animals for transport. The German motor park could only field 23,000 transport vehicles, but the shortage of rubber meant that they had to drive on steel tires, which destroyed the roads. Oil consumption had pretty much doubled in all countries, but Germany had imported 90% of its oil even before the war. They had to reach for Romania and even as far as Baku to remotely keep up with the everyday demands in petrol and lubricants.

Throughout the war, all sides relied on a sophisticated supply system to keep the war from stopping dead in its tracks, so the trenches cast a long shadow backwards, all the way to the workbench of the munition industry, or the nitrate mines and oilfields on the other side of the world. The Great War was not just the war of the common soldier, that went into the fight, rifle in hand. It was also the war of financiers, of manufacturers and bureaucrats, without whom the soldiers at the front would have to resort to fighting with sticks and stones. Modern war demanded a long supply chain, from the factory to the front. In the end, the mud-caked face of the tired soldier in the trench was not that different from the canary – the woman whose skin turned yellow from working tirelessly through the night with toxic chemicals to make shells.

The horrors of trench warfare reached far behind, even to those that were seemingly at a safe distance from the artillery and sniper fire. Angels were not just calling for names, they were calling for shells, butter and shoes.

Trench warfare in World War I heavily inspired our song ‘ Angels Calling ‘, which is featured on our album, Attero Dominatus. Take a look at the lyrics we wrote here.

Watch our second episode about trench warfare, titled Angels Calling Pt. 2 – Guns, Gas and Steel, here: