Night Witches

Female Soviet Pilots

The large-scale industrialisation of the Soviet Union in the late 1920s and 1930s opened up the country’s economy for women in the workplace, and there was no job for which a woman could not apply.

Soviet propaganda wanted them to join the workforce and steer the great machines of modernisation, and the most fantastic symbol of that particular age of machines was the airplane. Many were inspired by Soviet heroine Marina Raskova, who set world records for long distance flights, showing what pilots and planes from the Soviet Union could achieve. Newly emerging and quite popular flying clubs were also a chance for many women to escape the monotony or the poverty of their homes and learn how to become an aircraft mechanic or even a pilot themselves.

The summer of 1941

Fast forward to the summer of 1941. Weeks after the German invasion, hundreds of thousands of Soviet women flocked to the colours, enlisting as nurses, signallers or anti-aircraft gunners. The experienced female pilots of the flying clubs served as instructors and advisors for male recruits but were not allowed to fly into combat. The argument was that there were enough male pilots available.

Marina Raskova however, was determined to make a difference. With her influence in Moscow’s political circles as a Hero of the Soviet Union, she appealed to Josef Stalin himself and got permission to create three all-female flying units. The 586 Fighter Regiment, the 587 Heavy Bomber Regiment and the 588 Night Bomber Regiment.

Raskova was a natural leader and her call for volunteers was soon answered by hundreds of young women from all over the Soviet Union who were hoping to break into the ranks of elite female pilots.

By mid-October, as confusion and chaos swept Moscow in the face of the rapid German advance, Raskova had set up her training camp at the large aerodrome in the city of Engels on the Volga River. There, the women of the three regiments were to be trained with planes, engines, armaments and aeronautical studies and military drills. While college-educated women were trained as navigators, those with factory or armoury experience would work as mechanics.

The fighter regiment

Naturally, all volunteers wanted to become famous fighter pilots themselves, but only the most talented and experienced pilots were accepted into the fighter regiment. They needed lightning quick reactions and the ability to remain calm in battle. The professional pilots with many hours of experience were put into the heavy bomber regiment, led by Raskova herself. Those with less experience were put into the Night Bomber Regiment – these women needed the greatest courage of them all.

The night bombers were to fly the Polikarpov U-2, a flimsy biplane compared to the modern dive bombers. It had been designed and manufactured since the late 1920s and was used most often as a training plane. It had two cockpits, one for the student and the other for the instructor. It was a small and slow aircraft, made from lightweight plywood and percale, which was finely woven fabric made out of cotton. It was cheap to manufacture, unimpressive and outdated, but nonetheless a reliable workhorse for transporting the wounded, dropping supplies or reconnaissance flights. The Soviets nicknamed it the ‘Crop Duster’ or the ‘duck’, while to the Germans it was to be known as the ‘sewing machine’ or the ‘Plywood Russ’. Since it was totally defenceless and too slow to outrun any of the German fighter planes, it could only operate in the safety of the night. In fact, even small arms fire could bring it down easily. But the overall situation was so bleak, that even those little planes became symbols of hope and resistance.

Over time, the women began to appreciate the simplicity of the ‘Crop Duster’, especially since the women of the heavy bomber regiment had to fly the SU-2, which was nicknamed ‘The Bitch’ because of how difficult it was to master.

Despite Soviet theoretical ideology of equality between the sexes, Russian machismo was merciless. Wearing boots, tunics and greatcoats way too large for them, since they were designed for men, the women were constantly mocked and teased by their male counterparts for their lack of femininity. This only hardened their determination, since to them a soldier was a soldier. Raskova ordered the women to crop their hair and the battalion’s commissar forbade anything she perceived as ‘girl talk’ and prohibited any sort of flirtatious behaviour.

Preparing for combat

By late May 1942 they were finally equipped with enough U-2 aircraft to prepare for combat. By summer, they left the aerodrome for the southwestern front to meet the German advance on Stalingrad and the Caucasus. As Axis forces were advancing on Rostov, Raskova’s night bombers hit the German ammunition and fuel dumps, the vehicles and the ground troops. It was the navigator’s job to find the target and close in on enemy lines, then the pilot would turn off the engine and silently glide through the night. The first planes would throw down flares to illuminate the targets and the loads would be dropped. Then, they would turn on their engines and escape before the Germans could fight back.

The U-2 were converted to bombers by simple, and at first improvised, attachments. A bomb load of up to 300kg was slung under the wings. This was not enough to inflict significant damage, but that wasn’t the main purpose of the night bombers. They were to constantly harass the enemy, to deprive them of sleep and wear them down to grant them no rest periods. For that, the Germans hated them. After learning that the night bombers were usually piloted by women, they would give them their famous nickname: the Nachthexen – the Night Witches.

Every morning the women came back with red faces and bloodshot eyes. They rebuilt their lives around the night, having dinner in the morning and going straight to bed. They were constantly tired and hungry, but they were beyond proud of showing the Soviet Union that women could fly as well as any man, and with every successful mission, they earned more respect from the male pilots and officers.

But that would not protect them from the constant danger they faced. They had no parachutes, since Soviet high command figured that in the case of engine failure, the planes could simply glide back to earth. This totally disregarded the fact that the percale cotton fabric and plywood frame was highly flammable and could cause both pilot and navigator to burn to death. To Soviet High Command, that was still preferable to being captured alive by the Germans. In fact, those who were shot down or crashed behind enemy lines were expected to fight to the death, as capture was “dishonourable” to any Soviet soldier and would leave a stigma for the rest of their lives. Even pilots who were shot down behind the lines but hid and made it safely back to their own lines were interrogated and often condemned to death by the commissars.

Raskova’s legacy

On January 4, 1943, Raskova died in an accident on her way to the Stalingrad Front, but the 588 was determined to live by her ideals, and as one pilot wrote: “[It was] a time for bombing and bombing.” The Soviet counterattack prompted the hasty withdrawal of the Germans from the Caucasus and gave the Night Witches more than enough opportunities to harass and attack the retreating troops.

On January 4, 1943, Raskova died in an accident on her way to the Stalingrad Front, but the 588 was determined to live by her ideals, and as one pilot wrote: “[It was] a time for bombing and bombing.” The Soviet counterattack prompted the hasty withdrawal of the Germans from the Caucasus and gave the Night Witches more than enough opportunities to harass and attack the retreating troops.

From the steppes near Stalingrad to the high mountains of the Caucasus, the praise for the Night Witches grew. The freezing winter nights, through which they flew at high altitudes with open cockpits, did not discourage the women from fulfilling their missions. In fact, only once were they forced to remain grounded for a time.

On the night of July 31, 1943, during the German counteroffensive on the Taman peninsula in Novorossiysk, the Night Witches approached the German positions and noticed that the anti-aircraft batteries were strangely silent. Suddenly, flares lit up the skies. It was a German night fighter attack, and in moments, U-2 planes were falling from the heavens and burning to the ground. The survivors broke off, scattering back into the darkness.

Such high casualties in one night were a shock to the regiment, but one that didn’t last long. The war that eventually turned against the German invaders brought the Night Witches further to the west. To Cuba, to Krim, to Belarus, to Poland and eventually to Germany itself. Sometimes they made up to a dozen sorties a night, with only a few minutes of breaks in between.

There are many stories about these young women, who came from many different backgrounds and who did share their own personal tales of heroism, tragedy and idealism. “We were young and fearless. The fear came later,” one of the survivors would recall.

After the war, and after the regiment was disbanded, their commissar, Yevdokya Rachkevich took it upon herself to personally search for the crash sites of every last one of her lost fliers, to provide an accurate history of the regiment and the women that served and fought with it.

A total of 261 women served as Night Witches during the lifetime of the regiment, of whom 32 died in service. The strangest incident involving the regiment was the arrest of two of their mechanics for taking apart a flare and making undergarments from the small parachute inside. In total, 26 women from the regiment were awarded military honours for their service – 23 were conferred the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, two became Heroes of the Russian Federation, and one, a Hero of Kazakhstan. Major Yevdokia Bershanskaya, who commanded the 588th Night Bomber Regiment, received the prestigious Order of Suvorov medal, the only woman ever to have done so.

Read more about the life and career of Major Yevdokia Bershanskaya.

Other notable regiment members included Yevdokia Nosal, who was the first member to be awarded the “Hero” title and the first female pilot to receive it posthumously, and Irina Sebrova, who with 1,008 sorties was the regiment’s most prolific member. The regiment was the only one out of the three female regiments launched by Major Marina Raskova that remained entirely composed of women and never recruited a single man.

If you prefer a visual representation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode: Night Witches – Female Soviet Pilots.

Female heroes in battle

The Night Witches were considered fearless Soviet heroes, but they weren’t the only women that dedicated their lives to their countries.

Lyudmila Pavlichenko

When Lyudmila Pavlichenko was a teenager in Kiev, she joined one of the many paramilitary clubs of the Soviet Union. These were not only to keep reservists in shape, but were also open to the public. Pavlichenko was a born athlete and a natural with the rifle. She trained hard to outshine the boys and she earned her marksman certificate and sharpshooter badge with ease.

During the late 1930s, she enrolled into Kiev University to study history and aced a sniping school of the Soviet Red Army.

In the wake of the German invasion in June 1941, Pavlichenko was among the first female volunteers to stand in front of the recruiting office in Odessa. At first, they urged her to become a nurse, but Pavlichenko insisted that she wanted to fight with the infantry. A quick examination of her badges and certificates was enough to convince the recruiters, and she was sent to serve in the 25th Chapayev Rifle Division. She was to become one of 2,000 female snipers in the Red Army during the war. Only 500 would survive.

Her story goes that while her division was awaiting the advance of Axis forces on Odessa that summer, they sent out snipers to harass the enemy. At first, Pavlichenko was paralysed by fear as the Axis advanced on her position, but suddenly the young man next to her was killed by an enemy bullet. That snapped her out of the fear. She took his scoped Mosin-Nagant bolt action rifle and scored her first two kills of the war. These were to be the first of many. In just two and a half months of fighting for Odessa, she is said to have killed 187 Axis soldiers.

After Odessa fell in October, Pavlichenko’s unit was taken back to Sevastopol on the Crimea, awaiting yet another siege. By May 1942, she had really made a name for herself and was promoted to Lieutenant after making her 257th kill. She was sent out on ever more dangerous missions, including Counter sniping, which was a duel to the death with enemy snipers. Pavlichenko killed 36 of them.

After being hit in the face by mortar shrapnel in June, Soviet High Command took her out of the line. She was a well-known hero and was now too valuable to lose in combat. She was ‘Lady Death’, the female sniper with an official total of 309 kills.

Once she left the hospital, Pavlichenko became a propaganda tool. She was sent overseas to Canada and the US on a publicity tour and was the first common soviet citizen received at the White House. Pavlichenko spoke freely to the crowds about her experiences at the front; how the man she loved was killed soon after their marriage and of the terror the Germans had inflicted on her home.

But while the public found this interesting, the press seemed typically more concerned about the length of her skirt, the look of her masculine uniform and if the “Girl Sniper” wore make-up at the front. Pavlichenko remarked that the Americans should worry less about the looks of the uniform, and more about what it represented.

Virginia Hall

Although Virginia Hall had lost her leg during a hunting accident in her youth, that had not deterred her from pursuing a career in travel. Hall spoke several languages fluently and had a keen interest in European politics, but when she applied to become a diplomat overseas, the US Department of the State was reluctant to hire a handicapped woman. Hall, however, was determined. In 1940, while most of the American public refrained from having anything to do with the war in Europe, Hall was serving as a volunteer ambulance driver in France. Retreating from the German invasion, she heaved wounded French soldiers into her truck, driving them to safety under a constant threat of attack from the air. After France fell, she escaped to Spain, where she made the acquaintance of a British Intelligence Officer. The officer was intrigued by Hall’s dedication to fighting Nazis and put her contact with the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) in London.

The SOE was trying to infiltrate occupied Europe, but so far, the 50/50 chance for agents to survive the first weeks after insertion did not bring in many enthusiastic volunteers. Although the agency was reluctant to deploy a handicapped woman, they decided to put Hall into Section F – France. By April 1941, she had been inserted into Vichy France and occupied a safe-house in the city of Lyon. Her cover was that of a reporter from the New York Post who was there to gather stories about life under the new regime.

The first thing she had to learn was to move around without being suspicious. She had various outfits and hairstyles prepared, and made use of heavy make-up and disguises when she needed to turn into a different person for a while. It was doubt that kept her alive, and a strong sense for danger was her best ally. Hall knew when to lay low, when the French police was raiding houses or watching meeting points of suspected SOE agents. Double-agents were everywhere. Nonetheless, she soon built up her own network of informers and worked closely with the French resistance.

Over the winter of 1941/42, she used a brothel to hide exposed agents or British pilots that had been shot down over France before smuggling them out to Spain. Her most famous feat was an actual prison break, where Hall’s network freed several agents from a French prison. By mid-1942, her activities attracted more and more attention from the German secret police, and after the prison break stunt, they began cracking down hard on the resistance movements, for which Lyon became a hotspot. Hall even attracted the attention of Gestapo leader Klaus Barbie, known as the ‘Butcher of Lyon’, who supposedly said that he ‘couldn’t wait to get his hands on this limping bitch’.

After the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942, France became too dangerous for Hall, and she fled the country. She then joined the OSS – American intelligence. Although the OSS was at first reluctant to employ a handicapped woman, by 1944 Hall was back operating in France. Disguised as an old woman, she supported several resistance groups and prepared safe-houses for agents in the south of France until the Germans retreated. Virginia Hall had survived far longer than many other agents and she laid the groundwork for many espionage techniques that are still in use today. But she had to fight hard to do it, not only against the enemy, but against all the doubt from within the ranks of her own.

Simone Segouin

Before the war, Simone Segouin had lived a normal teenage life southwest of Paris. Her father had been politically active in her hometown and was very vocal against the German occupation. She greatly admired his patriotism. He had fought in the Great War as a volunteer, and for this war, she was determined to do her part. The Germans conscripted her to work as a seamstress in Paris, a big mistake in hindsight because in her workplace she made contact with members of the underground resistance. They fixed her a fake passport under the name of Nicole Minet from Dunkirk. Her first mission was to prove herself to the resistance and steal a bicycle from a German officer. She then used that bike to transport secret messages between resistance members in the town of Chartres. As a young woman, she was less conspicuous and had an easier time moving among the German soldiers than a man would.

Always on the lookout for high profile targets, Segouin was soon involved in several sabotage and demolition missions in the area. The young, courageous and reliable woman made such an impression on the resistance fighters that they trained her in the use of firearms. As the war neared its end, Segouin’s unit took to street fighting the retreating German soldiers during the liberation of Chartres. Segouin, sub-machine gun in hand, assisted in arresting 25 German soldiers. Then, the renowned war photographer, Robert Capa, came upon her unit, and he took the famous picture of Simone Segouin with her German sub-machine gun. Segouin soon became a symbol for the young generation that fought against the German occupation, for resistance valued courage and activism, no matter the gender.

Milja Toroman

In the winter of 1943/44, the renowned war photographer, Zorz Skrygin, travelled through the region of Kozara in western Bosnia. There, he encountered a group of guerrilla fighters. By this time, large parts of Yugoslavia had come under effective control of partisans, who fairly successfully fought the Axis occupation. Skrygin approached the partisan leader and asked if he could take pictures of the group. Among the female medics was the 17 year old Milja Toroman, a Bosnian Serb who grew up in a small village near Mount Kozara.

Wearing a cardigan, Milja swung a rifle over her shoulder, adjusted her Titovka cap and smiled as she turned her head. At that moment, Skrygin took the photo. In 1968, long after the victory of the partisans, Skrygin published this photograph in a book of his war photography. There, Milja became “Kozarcanka”, the girl from Kozara. Skrygin simply described her as a young girl who had fled German captivity and joined the partisans to fight the fascists.

The photograph was a huge hit and Kozarcanka became a Yugoslavian icon. She embodied the partisan struggle and was a perfect fit for the propaganda of the Communist Yugoslav state. She was a symbol that despite the dangers of the war, the partisans remained enthusiastic about their coming victory. Kozarcanka’s smile expressed confidence and optimism. Her girlish innocence contrasted by the rifle across her shoulder. The true identity behind Kozarcanka was not ever revealed until the collapse of Yugoslavia.

Although it was a staged photograph, Milja still remains a symbol not only of the struggle of the Yugoslav partisans and the many women that fought in it, but the many women who fought for their beliefs, there nations and their freedom during that great conflict.

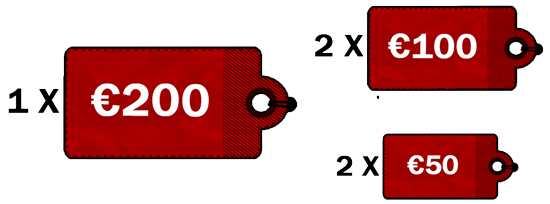

The incredible story of the Night Witches and women in battle heavily inspired our song ‘Night Witches‘ which is featured on our Heroes album. Take a look at the lyrics we wrote here.

If you prefer a visual representation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode: Night Witches Pt. 2 – Female Soldiers.