The tale of the Red Baron

Known the world over as the Red Baron, Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen is one of the greatest symbols of World War I. He was born on May 2, 1892, in Silesia to Prussian nobility. His father was an officer of the Imperial German army.

Manfred enrolled into Wahlstatt military school at the young age of 11. He would rise to the rank of lieutenant in the 1st Uhlans, a prestigious cavalry regiment. However, when the war came, cavalry would not play a major role on battlefields dominated by machine guns.

To escape the monotony of guard duty in the trenches, von Richthofen looked to the skies, where the first reconnaissance planes flew. He successfully applied for the air service in June 1915 and began his work as an observer in a two-seater on the Eastern Front, photographing Russian troops. He was then transferred to Belgium.

Airplanes evolved rapidly during the war. By late 1915, the days of unarmed reconnaissance planes were over and the single seater fighter appeared over the battlefields, as did the first German flying aces – an ace being someone with five confirmed aerial kills. By early 1916, men like Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke made names for themselves as the “knights in the skies” and were the first airmen to be awarded the Pour le Merite, Germany’s highest military honour. They were huge stars; the public loved them and the enemy feared them. And of course, their image made an impression on young men such as von Richthofen, who wanted to be just like them.

Jasta

This was the period of the Fokker Scourge, as, thanks to Antony Fokker’s synchronisation gear, German pilots were able to fire through their propellors and aim the gun by aiming at the plane, and this changed how aerial warfare was conducted. Fighting in the sky reached a new level of intensity. By mid-1916, the allies had caught up with the aerial arms race, and over the skies of Verdun and the Somme, vicious dogfights took place. Oswald Boelcke and German Chief of Field Aviation, Major Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen, had a new idea to maximise the effectiveness of the German air force – the Jagdtstaffeln. Called Jasta for short, this combined several planes into a unit that fought together and attacked the enemy in concert.

Boelcke would personally lead and train Jasta II, and he handpicked his pupils, one of which was Manfred von Richthofen, though it is unclear what Boelcke saw in von Richthofen, who had an unremarkable flying career and who crashed the first time he had flown a fighter plane.

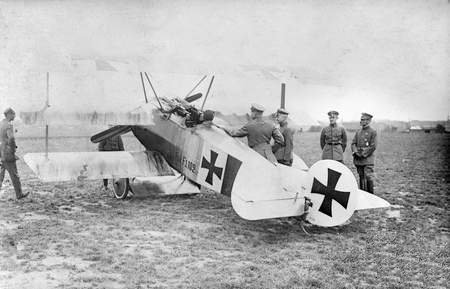

Jasta II, or Jasta Boelcke as it became known, fought in Northern France near the Somme. The pilots could usually choose their own planes at the time, either Fokker D.III, Albatros D1 or the new D2. On September 17, the Jasta was operational and Richthofen got his first official aerial victory. Boelcke had 8 principles to guide his pilots entitled the Dicta Boelcke, and he had a huge impact on German air strategy, but he met his fate October 28.

Nearly a month after that, Richthofen’s legend began when he shot down British ace, Major Lanoe Hawker. Richthofen had embraced Boelcke’s teachings and raked in victory after victory by diving, whirling and accelerating – it all came naturally to him.

Following his 17th victory, von Richthofen was awarded the Pour le Merite on January 12, 1917, and given command of his own Jasta, Jasta 11. He brought in the Dicta Boelcke and would lead the Jasta by personal example.

Richthofen is often portrayed as the single hunter of the skies who flew mostly on his own in his bright red Fokker triplane, but his true merit was as commander of his Jasta. He was as skilful as an organiser, teacher and leader as he was a killer in the skies. Under his command, new aces emerged, such as Kurt Wolf, Werner Voss and Manfred’s own younger brother, Lothar von Richthofen.

As spring arrived, they were equipped with the new Albatros D.III, and what was known as ‘Bloody April’ began. Over the skies of Arras, the Jasta went to work like predators stalking prey, fighting aggressively and systematically. It was truly a Bloody April, as Jasta 11 scored 89 confirmed victories alone. Richthofen shot down 21 planes that month and had, by that point, surpassed Boelcke.

The German press was ecstatic and Von Richthofen’s fame rose to unprecedented levels. The newly promoted “Rittmeister” got world-wide attention. He was the “Red-Baron”, the “Petit-Rouge”, the “Rote Kampfflieger”, because of the bright red of his planes. In the skies, there is no need for camouflage and in battle it paid to be recognised. Richtofen himself said: “I make sure that my squadron sees me wherever I am.”

Brightly coloured birds

Like their commander, the men of Jasta 11 painted their planes in bright colours and distinct patterns. One was yellow with a black tail, another green and dark brown. One had blue stripes, another a chequered pattern on the tail. Standing next to each other they looked like brightly coloured birds. To friend and foe alike, the Jasta became known as Richthofen’s Travelling Circus, as it was always sent to where the fighting was heaviest.

They wanted to be seen by their enemies, by their comrades and by the men on the ground. They would strike fear in their enemies’ hearts. The famous red plane emerging from the clouds was terrifying for a new allied pilot. Friendly fire also happened a lot, especially during the bigger engagements, and the bright colours distinguished the Jasta from their enemies. Also, the men on the ground, who watched cheering from their trenches, could make out who made a kill. A victory in the sky had to always be confirmed in the German aviation service. If no-one witnessed it, then it didn’t count towards the tally. And since there was natural competition between the young men, this was considered important.

Richthofen was a caring mentor to his “pups”, and as the pilots returned after each mission, he would meet them with both praise and lessons on how they could further hone their craft. He was beloved by many and highly respected by all. However, the pilots under Richthofen’s command were not invincible. The allies had experienced veterans and aces of their own, and many German aces fell prey to allied machines.

As Bloody April passed, the balance shifted once more towards the allies, with their fighters like the SE5 and the Bristol F2B. To counter this and increase the effectiveness of the Jagdstaffeln, they were combined to the even bigger Jagdgeschwader hunting-squadrons. The first squadron, consisting of Jasta 3, 4, 11 and 33 was placed under the command of the Red Baron. This comprised 50 to 60 planes that could quickly be transferred around the front.

Flanders

In Flanders during the build-up for the Battle of Passchendaele in the summer of 1917, British artillery was giving the German infantry hell. It was directed by reconnaissance planes, accompanied by bombers and fighters, who were strafing the Germans on every run. Jagdgeschwader 1 was sent to try to gain local air superiority. On July 6, von Richthofen led the mission and they encountered an enemy bomber squadron. As the Red Baron positioned himself behind a British bomber, something hit his plane, ricocheted off the frame and hit the Baron in the back of his head.

Nearly unconscious and with blood pouring from the wound, he broke off the attack but the hit temporarily blinded him. He didn’t panic and calmly turned off his engine. There was nothing he could do until the shock wore off and his sight returned. His plane had lost altitude by then, but two other pilots had guarded their commander from the enemy. Richthofen turned his engine back on and made his way back to the airfield. Who or what hit the Red Baron that day remains a mystery to this day.

Richthofen did not return to his men until mid-August, his head still bandaged, but from hospital he had contacted high command about new planes. The British, with their new Sopwiths, had the upper hand, while the German manufacturers hadn’t produced something new in months. On his return to the squadron, Anthony Fokker himself was there to greet the Red Baron with the new Fokker Triplanes, the Fokker V4 prototypes. Fokker of course, used that meeting as a PR-coup, filming the Red Baron in the new triplane, another reason why the triplane became so associated with the Red Baron, but Richtofen “only” scored a fraction of his total victories in the triplane.

The plane’s reception was mixed, however. It was way more manoeuvrable than the biplanes, but not much of an improvement in terms of speed. Von Richthofen wasn’t too happy about the prototype, especially now that the enemy’s advantage in numbers was growing more than ever. As 1918 began, German high command wanted to see their star safe and sound, but the Red Baron could not be contained, and the German Spring Offensives needed their best pilots to succeed.

In April 1918, von Richthofen pushed his machine to its limits, scoring 12 victories in just 2 weeks. It was Bloody April all over again, but the fighting and the head wound took their toll. Richthofen became exhausted and isolated himself more and more from his peers. On the 21st, one day after he had scored his 80th victory, von Richthofen flew out again.

At 10:30 his men engaged the Australian Flying Corps over Cappy. Richthofen was seen chasing a Camel Scout. Uncharacteristically, against his own teachings, he pursued the fleeing Scout along the Somme valley, deep into enemy territory. Canadian ace Captain Arthur Roy Brown spotted Richthofen and dove behind him, firing a burst at the Baron’s tail.

At 10:30 his men engaged the Australian Flying Corps over Cappy. Richthofen was seen chasing a Camel Scout. Uncharacteristically, against his own teachings, he pursued the fleeing Scout along the Somme valley, deep into enemy territory. Canadian ace Captain Arthur Roy Brown spotted Richthofen and dove behind him, firing a burst at the Baron’s tail.

Richthofen went down in a beet field and the red triplane came to a stop. The Red Baron was dead, killed by a single bullet through the heart. Captain Brown is officially credited for bringing down Richthofen’s plane, but it is more likely that the Baron was hit by fire from the ground, as he was flying fairly low. But to this day, there is a lot of speculation about the exact circumstances of his death. The news reached the Jasta after they had already begun searching for him and German high command even sent out an official request to the allied high command, inquiring about the fate of the Red Baron.

Manfred von Richthofen was buried by the Allies with full military honours, accompanied by an honour guard of officers from the Australian Flying Corps. His aircraft was taken apart for souvenirs, and even small pieces of the bright red canvas were considered valuable. Some are still on display in museums in Britain, Australia and Canada.

Despite the death of a hero, the legend of the Red Baron was and still is very much alive.

People may not be familiar with the Kaiser, the battles or anything about World War I, but they still recognise the name Red Baron. And now, over a hundred years after his death, Manfred von Richthofen is still strongly represented in books, films and songs.

If you prefer a visual representation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode: The Red Baron – The Great War.

Episode 1

The Price of Flying

Like The Red Baron, there were other flying aces who had skills, resilience and valour in the skies. We present to you the stories of Adolphe Pégoud, Charles Nungesser and Rudolf Berthold.

Adolphe Pégoud

Considered the grandfather of modern flying, the passionate French aviator, Adolphe Pégoud, pioneered several aerial manoeuvres in the years prior to the Great War. He was the second pilot to fly a loop and the first to successfully make a parachute jump from his airplane. Aspiring pilots from all over the continent flocked to his training school, all wanting to learn the art of flying from the famous test pilot. Back then, the idea of destroying such wonders of technology as airplanes on purpose was simply an insult to mankind’s ingenuity, but then the war came and mounting a machine gun on everything that could move eventually turned those technological marvels into weapons of destruction.

By April 1915, Pégoud had claimed six aerial victories. In those early days, a “kill” meant “causing the enemy to fall” or “forcing the enemy to land”, not necessarily an actual kill.

He became an ace before being an ace was even a thing. The French press proudly called Pégoud “L’as de notre aviation”, which translates inti “the ace of our aviation”, and the “Roi du ciel” – the “King of the skies”. But the master of aerial acrobatics was shot down soon after, killed by one of his former students from Germany. What Pégoud and his peers had begun would usher in the era of the flying ace. The pilot life attracted men who sought the thrill and constant danger of aerial combat, where the outcome was usually determined by skill and ability – but it all came at a high price.

Charles Nungesser

It is said that once Charles Nungesser had joined a French flying squadron, known as an “escadrille”, in early 1915, he never missed a chance to take to the skies. Even in bad weather, he roamed the battlefields for hours, spoiling for a fight. With the advent of agile monoplanes, Nungesser began to make a name for himself as a daring pursuit pilot, flying deep into German territory to seek out the thrill of combat.

But Nungesser was easily as much of a headache to his own officers as he was to the Germans. He hated military discipline and his fighting style was unorthodox to say the least. One of his favourite manoeuvres was the “hip-stall”. From high above, Nungesser would dive down on his enemy with insane speed until he was slightly under him. Then he would pull the plane up, firing into the underside of the enemy plane. A tactic that was deadly when it worked, but also very dangerous if it didn’t.

By 1916, Nungesser needed a cane to be able to walk to his plane. He was plagued by several lasting wounds and healed broken bones, and had collected as many scars as he did medals. The public, however, loved him for this reckless image.

Charles Nungesser was the poster child of the heroic, charismatic flying ace of the time. When he wasn’t flying, he enjoyed the thrills of fast motorcycles or the Paris nightlife. He was a playboy, renowned in the French party scene and rumour had it that he had an affair with Mata Hari, the alleged famous spy. It wasn’t unusual that he would wear his tuxedo from the night before as he entered the aerodrome.

When he was outfitted with a Nieuport 11, he began decorating his plane with his soon-to-be-famous emblem: a skull and bones underneath a coffin, flanked by two candles in a black heart. Like all aces he wanted to be seen by both friend and foe in the skies and on the ground. In fact, a British novice pilot once nearly shot him down, probably mistaking his markings for a German Iron Cross. Nungesser then went on and painted his plane in bright red, white, and blue colours, just to be safe.

Legend has it that by the end of 1917, the Germans had a bounty of 500,000 Deutsche Marks on the pilot with the coffin, but they still failed to shoot him down – a group of five Fokkers shot his plane to pieces, but Nungesser survived.

By the end of the war, he claimed 43 victories, yet his medical report at the end of his career highlighted what it took and what it cost to be one of the best flying aces of the Great War:

“Skull fracture, brain concussion, multiple internal injuries, five fractures of the upper jaw, two fractures of the lower jaw, a piece of anti-aircraft shrapnel imbedded in right arm, dislocation of knees, bullet wound in the mouth, bullet wound in the ear, dislocated clavicle, dislocated wrist, dislocated right ankle, loss of teeth, contusions too numerous to mention.”

Rudolf Berthold

Rudolf Berthold’s story was in many ways similar but yet quite different from Charles Nungesser’s. Like many young pilots, Berthold romanticised the freedom of flying, despite the many lethal dangers. For him it was the most beautiful experience in the world – a way to leave earthly boundaries behind. Aircraft were still a technological novelty, but their usefulness in war was growing with each technological jump. The German Flying Corps was quite late to the game, but by September 1915 they had established their own monoplane fighter initiative: The “Kampf-Einsitzer-Kommandos”. And young pilots such as Rudolf Berthold were eager to prove their mettle.

By April 1916, Berthold had shot down his fifth enemy, officially entering the ranks of the aces. Five victories may not appear to be many to some, but in those days, coming back from a flight was never guaranteed. Young and inexperienced pilots died first and died in droves, and those who actually made it to five victories in the air were considered the elite.

The dangers of not coming home became a constant in Berthold’s career. During a test flight of the flawed Pfalz Monoplane, Berthold’s engine began to stall shortly after his take off. The plane crashed hard into the ground and Berthold hit his head against the wrecked cockpit. Suffering a broken leg, a dislocated jaw and temporary blindness, he was in such pain and despair that he begged his men to shoot him.

Berthold survived, ironically recovering in a hospital next to a British pilot he had shot down the day before. As news of the Battle of the Somme reached the hospital, he dragged himself out of his bed. The doctors urged him to stay, but Berthold had an iron sense of duty. His leg may not have functioned properly but he could still fly and fight for his country.

Berthold’s skill in the air soon gave him his first command. Similar Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron, Berthold was to be in charge of one of the new hunting squadrons, the Jastas. Instead of red, he chose to paint his plane bright blue, and his Jasta was soon known as the “Blue Birds”.

Berthold’s skill in the air soon gave him his first command. Similar Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron, Berthold was to be in charge of one of the new hunting squadrons, the Jastas. Instead of red, he chose to paint his plane bright blue, and his Jasta was soon known as the “Blue Birds”.

But unlike the Red Baron, Berthold was a harsh teacher. For him, “accomplishment was born only out of inner joy”, and those whose life did not fully revolve around flying would always remain flawed pilots.

The emergence of the Albatross planes, with their sleek bodies, synchronised machine-guns and powerful compression engines began the high tide of German flying aces. But like Nungesser, the constant state of combat took a heavy toll on Berthold’s body. He had achieved 10 victories by the time he was 26 but was a mess of injuries and broken bones. Still his urge to be a selfless example to his men dragged him back into the cockpit time and time again despite the pain it brought him.

His peers gave him the nickname “The Iron One”, for his spirit seemed to be made out of unbreakable metal. He was also often overcome by deep depression and sometimes fell into erratic behaviour. He was prone to towering rages, only to be full of laughter a few hours later. His mood swings can likely be linked to the large quantity of narcotics he had to take to deal with the pain of his injuries. At the time, three major painkillers were prescribed: Morphine, Codeine and Opium. Morphine was the most easily available but also the most addictive. To combat the drowsiness the drug inflicted, Berthold used cocaine to get his energy back. Drug use was not uncommon – it was war after all. But Berthold’s psyche began to suffer under the constant state of effect and withdrawal. Nonetheless, under his personal leadership, his Jasta was transformed into a well-oiled killing machine.

In October 1917, Berthold was shot down for a third time. Bleeding profusely, he managed to land before losing consciousness. His right arm was shattered, a mess of fractures that would take months to heal. Berthold, however, could not be kept in a hospital bed for long. Declaring “If I can write with my left hand, I can fly with my left hand.” He fled the hospital once again, just in time for Germany’s big Spring Offensives in March 1918. He almost felt a compulsive responsibility to lead his men into battle. “If the war became more like iron”, he said, “so must I.”

By May, his mechanics had to carry him to his cockpit. His right arm was still paralysed, but the control schemes of the new Fokker DVII allowed him to fly with just the left. In just 10 minutes after leaving the airfield one day, he shot down his 30th and 31st planes. But of course, under such conditions, his wounds refused to heal. It is said that Berthold often screamed out in pain as he was flying.

The year rolled on. Germany’s offensive turned bad and so did the war in the air. Each time he went out, Berthold came back with more bullet holes in his plane. In August, just as he scored his 44th victory, his engine buckled. Descending quickly, Berthold tried to get out with the parachute, but the mechanism needed two hands to work and his right arm was still useless. Unable to stop, his plane smashed into a house, but although the crash was so bad that it threw the engine block from the plane, Iron Man Berthold survived.

In excruciating pain, a high fever and more broken bones, he was rushed to hospital. He managed to return once more to his aerodrome in early October, but he did not take off again. It was, however, the end of the war, rather than his own choice, that finally grounded him for good.

As history fanatics, the gripping tale of Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen truly impacted us as a band and heavily inspired our song ‘The Red Baron‘ which is featured on The Great War album. Take a look at the lyrics we wrote here.

If you prefer a visual representation of this story, watch our Sabaton History episode The Red Baron Pt. 2 – Kings of the Sky: