1648

After nearly 30 years of constant war, plundered cities and millions of lives lost, the warring factions were finally willing to return to the negotiation table in late 1646. No matter which side or religion, almost all duchies and estates were sick of the war. Not only because of the misery and the economic collapse of vast stretches of the Holy Roman Empire, but also because of the increasing futility and absurdity of the ceaseless struggle.

Many felt that the war hadn’t achieved any meaningful political goals for a while, and at this point in history, it was just about the interests of individuals. Even the majority of the German protestants and those allied with Sweden or France, who admittedly wanted the grip of the Habsburg Emperors loosened, realised that there was no real alternative to the Habsburg rule if they wanted to keep the empire alive in any meaningful sense. Those within the empire distrusted all foreign powers by now, after the devastation that had followed their armies marching time and again through countryside, through their homes.

Exploring the possibility of peace

Both the Catholics and the Protestants wanted to settle things. In Westphalia in the western part of the empire, the Catholics met at Münster and the Protestants at Osnabrück to debate the possibilities of peace. They sent each other envoys and letters, arguing for a common future within the empire. The Swedes were interested in northern Germany, with possessions that could safeguard the Swedish realm. Most of the northern German states had little choice but to pay tribute or ally with the Swedes, since the military might of the Emperor Ferdinand III was too weak to help them. By now, the military balance had clearly swung towards his enemies. The armies of Sweden and France now outnumbered the Habsburg forces in the south, while the emperor’s alliance with Maximilian of Bavaria lay in tatters. The Swedish army was still the mightiest in Germany, bolstered by many German regiments, with around 63,000 men at arms.

The second most powerful were the French, whose interests in the empire were far more complex than simply securing their own borders. They wanted the empire to bleed but at the same time needed to preserve the Catholic influence in Central Europe. This way, they opportunistically fought with and against the Swedes and with or against German duchies and contingents, depending on the strategic situation. Cardinal Mazarin, who represented the French in Westphalia, wanted to expand French territory, but more importantly, felt the need to cut Habsburg ties to Spain, which had just signed a truce with the Netherlands after 80 years of war.

The next few months were ones of constant debate. The big powers and the German cities, the estates, the dukes and knights, they all had their demands, and all wanted to have a say. They quarreled over jurisdiction rights, about compensation for war damages, about borderlines on the map. Who would pay for the troops to leave? Who would pay for them to stay? Who was rightfully owed money? Which unfulfilled promises, threats and boasts were still cause for concern? It was about reputation, about succession and hierarchy in the empire; about new alliances and old feuds; about persecution and amnesty.

Radicals and moderates tried to find a solution in religious matters and the property of the church. Militarist Calvinists wanted to fight on to the end, while radical Catholics argued that “a peace that enslaves souls is worse than a war that just kills the body”. It was a nightmare of haggling and bickering about the future of Central Europe.

Taking command

But while everyone was debating and arguing, there was one man who wasn’t the talkative kind, and instead relied upon the ways of the warlord. Swedish Field Marshal Carl Gustaf Wrangel had taken command over the Swedish forces in Germany. Not wanting to sit idly by while peace was on the horizon, he set out to fight against the southern coalition into Franconia. Wrangel’s tactics were by now common practices. He inflicted terror throughout the countryside by razing whole villages, shooting churches to pieces, trampling crops and fruit trees into the dirt, and of course, the usual excessive amount of murdering and raping among common folk who were unfortunate enough to stand in the way of his army.

Wrangel raided deeper into northern Bavaria, besieging and bombarding cities as he went. He plundered those he was strong enough to take, arguing that the more he could harm the Catholics, the weaker the Imperial position would be on the negotiation table. Wrangel was obsessed with the booty and treasure of the rich aristocracy and clerics, since that was how he and his officers made their living. Maximilian and Ferdinand were well aware of that, and in turn, hoped to bolster their forces enough once more to drive a wedge into Swedish forces descending on their territory.

The Battle of Zusmarshausen, though, in May 1648, ended with a Swedish victory, as the Imperials and Bavarians only escaped total destruction with maybe a few thousand men left. Wrangel’s ambition, on the other hand, and like so many men before him, had cost him his life. A pistol shot to the chest ended his career. But there was always someone to replace such a man and his ambition, and with the empire badly defeated on the battlefield, the Swedes wanted one more shining victory. Under field-marshal von Königsmarck, they set their sights on Prague, where the whole mess had started 30 years ago. A cynic would not have missed the irony in it all, as the Swedish army passed the old battlefield of the White Mountain, where the first battle of the war had been fought. The final one would be fought nearby.

Targeting Prague

Bohemia had long since been drained of troops, and Prague, though still a jewel in the German empire, was only held by a small garrison, now under the command of Imperial Field Marshal von Colloredo. The story goes that a disgruntled imperial lieutenant colonel, who had lost his arm in service of the Empire, showed the Swedes where the city’s defensive works were the weakest. And on the night of July 25, a hundred Swedes overpowered the defenders on the western side of the River Moldau, and gained entry into the “Little Town” of Prague. The gates were opened for the main host and a terrible plundering began. The old fortress Hradchany was taken, and the Swedes marauded through that half of the city.

But the city gates across the river were barred, and citizens and students there took up arms. In defiant firefights, they stopped the Swedish troops who came charging over the Charles Bridge. Colloredo’s garrison and Prague’s people were determined to defend the Old Town. Three times in this war, Prague had opened its gates to foreign invaders, and three times they had suffered. Enough was enough. Königsmarck soon realised that this was a tougher nut to crack than he had anticipated, but over the coming weeks, new Swedish contingents would arrive from Silesia and Saxony, drawn by the prospect of loot, while small imperial forces also snuck into the city to bolster the defences.

Even as three Swedish armies simultaneously attacked – one of which was led by the Crown Prince Carl Gustav, who had arrived to make his mark – the determined defensive would not be broken. From July to October, the siege dragged on. The situation for the defenders looked bleaker than ever. Colloredo knew that the inhabitants of Prague would face a terrible fate if the walls were taken, so every able man was expected to stand by the barricades, while women and children helped out were they could, putting out fires and caring for the wounded. It was all or nothing. Rich or poor, prince or pauper; they all fought together and would suffer together if they failed.

On October 6, the offensive was renewed. The Swedes were now building their own bridge over the Moldau, attacking the Galgen-Gate with all their might. They bombed it for two days until the gaps in it were large enough for the Swedish storm attack. Taking heavy casualties, the attackers eventually forced their way into the city. Only a desperate charge of Colloredo’s reserve drove the Swedes out of the city once more.

Prague prevails

Then on October 24, 1648, the news spread like wildfire through the empire: peace had been signed. The arguing and debating in Westphalia had finally come to a conclusion. A 70 gun salute at Osnabrück proclaimed the end of the war. On October 25, though, the Swedes attacked once more. If they ignored the peace treaty for just a few days longer, they could go home as rich men. But the desperate and exhausted defenders of Prague would once again deny entry to their city. By the day’s end, 800 Swedes lay dead before the breaches in walls and gates. It was not until November 5, as a large imperial contingent appeared outside of Prague, that the frustrated Swedes began to retreat. The siege was broken, Prague had prevailed.

In the peace treaties of Osnabrück and Münster that concluded the end of the 30 Years War, all factions had found a compromise that would guarantee lasting peace in Central Europe. A new imperial constitution acknowledged the rights of the protestants while keeping the Habsburg emperor in power. Sweden and France also profited from the weakness of the empire and extended their influence over Germany. There were smaller disagreements, of course, like who was the rightful owner of Alsace-Lorraine, and they remained unsolved.

At that point in time, all that counted was that 30 years of war – 30 of the most brutal years our world has ever seen – were over, and Central Europe was at peace.

If you’re interested in a more visual interpretation of the above story, watch our Sabaton History episode, 1648 – The Thirty Years War:

1648: War and Disease

1648 was the year the 30 Years War ended, and that war was not just marked by great violence, but also great outbreaks of disease. That year was also near the end of the endemic series of European plagues that began with the Black Death in the 1340s.

We are not too far past the centennial of the end of the Great War, one of the deadliest conflicts in the history of the world, where many millions of people died from bullets, shrapnel, gas, famine and disease. However, the death toll of that War was soon surpassed by that of a pandemic so deadly that it still lives strongly in our memory today a century later – the Spanish Flu.

The Spanish Flu

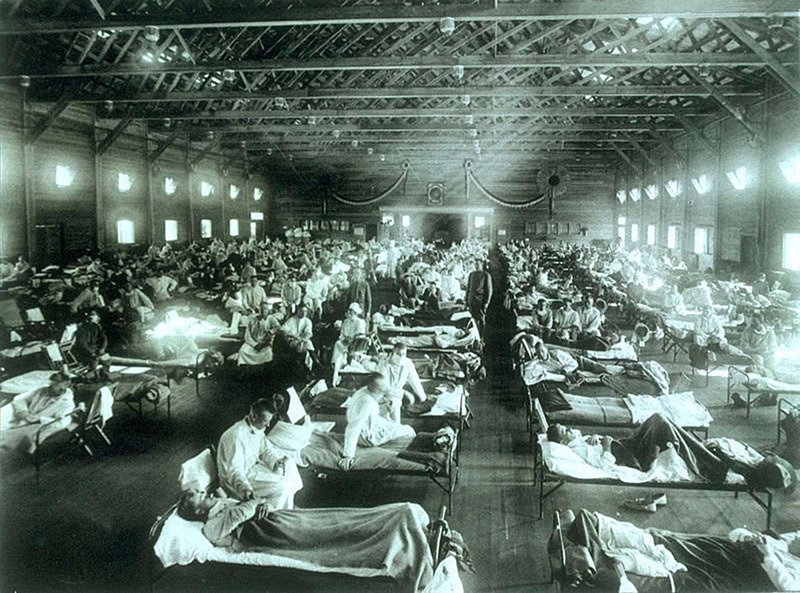

In the spring of 1918, the international news agency, Reuters, released the first reports from Spanish hospitals that they were seeing a communicable disease conceivably of epidemic proportions, and as the months rolled on, the death toll indeed grew to staggering numbers. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians had to be hospitalised.

A second deadlier wave of the Flu struck in the autumn, just as the war was reaching its end. Now, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive was the bloodiest battle for Americans during the War, claiming the lives of 26,000 US soldiers, but the flu killed around 45,000 more of them behind the frontline – and that figure is small.

Globally, for much of the fall of 1918, some 300,000 people were killed by the disease each day. Overall, more than 500 million people around the world, and possibly many more than that, would catch the flu, and the death toll lies somewhere between 40 million to 100 million people.

To this day, though, historians disagree on where it originated. Some say Kansas in the United States, others place it in China, or even in a field hospital in northern France. It was called the Spanish Flu or Spanish Lady by the news agencies because initially, only neutral nations like Spain reported it; the warring nations all had heavy censorship of anything that might damage morale, but that of course delayed the response of their health authorities.

Historians are also still unsure if the influenza had a decisive impact on the outcome of the Great War. To this day, laboratories run bacteriological and virological tests on preserved bodies from that era to better understand disease epidemics and pandemics. Theses about herd-immunity, mandatory quarantine and plague circulation are based on our experiences in the past, from times when vaccines or antivirals did not exist.

Two of the four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, war and pestilence, are seldom far from each other. Even in one of the earliest known works of literature, Homer’s Iliad, there is a plague of some sort. Scholars like Homer might have had a basic understanding of medicine, but his audiences did not, so the cause of the disease, which strikes the Hellenic armies in front of the Trojan walls, is of unnatural and divine origin. A kidnapped priestess evoked the anger of a god, which unleashed a foul miasma of death and disease to engulf the offender’s camps. Like being struck by invisible arrows, the Greek soldiers were cut down, and the funeral fires burned unceasingly. It is the explanation of an archaic and classical world trying to make sense of that which man could not combat. Bound by fear and hopelessness, they attributed the disease to the wrath of a higher power.

A millennium later, the mighty warriors of Athens, who faced Persian or Spartan armies without fear, were struck down mercilessly by disease during the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides describes the symptoms in detail: high fevers, swollen tongues, blistered skin, black throat and yellow spittle. The streets were filled with disfigured sick people cursing the gods, because they did not understand from whence their torment came. And the doctors died as quickly and as often as their patients. Wars could not be fought under such circumstances. Massed troops of men confined in camps and forts were an ideal breeding ground for any infectious disease, and epidemics drained the fighting strength of armies on a scale that no enemy could, and affected the civilian populations around them, sometimes on a gargantuan scale.

The Black Death

Medieval Europe was most devastatingly struck by the Black Death – the plague. While the word “plague” is used to refer to a “plague of something”, it is actually a specific disease, one of the deadliest and most virulent communicable diseases known to man.

Striking Central and East Asia in the 1330s and 1340s, and reaching Europe in 1347, it would continue to haunt the world for centuries to come. Pre-plague European population levels, for example, were not reached again until after 1500. But despite the chaos, humanity was making progress when it came to understanding pandemics. Physicians drew connections between people travelling and the epicentres of disease. To prevent sickness from spreading, authorities imposed sanitary cordons around affected cities and areas, placing them under quarantine.

There was still a lot of superstition. People took to religion to be spared or cured of the unknown sickness. Infected individuals were branded as “cursed” or “plague bearers”, and were denounced and shunned. Scapegoats, like minorities, criminals or perceived heretics, fell victim to bloody reprisals. Nonetheless, quarantines were the only way to effectively fight pandemics for a long time.

The Italian Plague

But in wartime, soldiers would still move from place to plague. The Italian Plague from 1629-1631 was part of a new wave of the Black Death, which was brought by travelling mercenaries during the 30 Years War. Cities such as Milan, Florence and Venice lost up to one-third or even half of their populations, and there was also a devastating economic recession. That plague might well have accelerated the downfall of Northern Italy as the economic powerhouse of Europe.

The world was not quite free from the plague even after that. During the Great Northern War at the beginning of the 18th century, East-Central Europe and the Baltics were struck by a strain of the plague. Coming from the southeast, it spread through Poland, Prussia and Scandinavia. The density of the big cities and trade hubs, as well as the massed armies marching the land, soon left whole areas ruined by the spread of the disease. Where the soldiers marched, disease followed. From the supply lines, contaminated goods were transported to local merchants. Marauding soldiers brought the plague to remote villages, and the cities, well-fortified to withstand even the strongest siege, succumbed quickly to sickness. Where the four horsemen struck, people suffered.

But humanity as a whole still survived and made further progress. Although medical record keeping was poor and diagnostic analyses lacked professional standards, in addition to the quarantines, specialised plague houses and plague-doctors were established to actively fight the spread of disease. For a time, even the whole Duchy of Prussia was put under quarantine and several Danish isles were isolated from the rest of the world. The well-known Charité Hospital of Berlin was built in 1710 in front of the city walls to fight another possible outbreak of the plague.

But looking at war and disease, until the end of the 19th century, it was common during any war that far more soldiers perished due to infectious diseases than from the actions of their enemies. The American Civil War is often studied in that regard, being a major, large scale war fought not long before the discovery of modern germ theory or bacteriology. Two-thirds of the deaths during that war can be attributed to the lack of proper sanitary conditions that were responsible for the spread of various epidemics. Even without a major pandemic, uncontrolled infectious diseases like pneumonia, typhus, dysentery and malaria caused hundreds of thousands of deaths.

The evolution of medicine

In the 20th century, major advances in medicine began changing that model. Vaccines and antibiotics began to prevent and treat diseases before they became such a huge problem. And although it had its fair share of trench-fever and outbreaks of typhus, malaria or other infectious diseases in areas such as the Balkans, Africa and the Middle East, the Great War did not have the epidemic disease numbers of major wars of the past. The horrible conditions in the trenches where men lived and slept for weeks on end in their own waste, the wounded men, rotting corpses, excrement, rats, flies, lice and fleas, would have led to major epidemics or pandemics in the past, but modern medicine and the advances in nutrition and sanitation mostly prevented that. At least it did until the Spanish Flu hit.

The story of The Battle of Prague heavily inspired our song ‘ 1648 ‘, which is featured on our album, Carolus Rex. Take a look at the lyrics we wrote here.

Check our our second Sabaton History episode for the song 1648 here: